I’m not sure about this, but it would be my guess that human beings have been looking for easier ways to do things since the dawning of human intelligence. I can almost imagine the ideas trickling into the head of Homo habilis’ as they foraged and hunted.However, I’m not sure that our early ancestors looked for shortcuts per say to their daily required chores and tasks. There is a difference between making life easier and taking shortcuts, that is. Again, I’m not sure about this, this is an informal blog after all, but it seems that making life easier transformed into taking shortcuts some time in the recent past.

The differences between making life easier and taking shortcuts at first glance seems little. But consider it for a while. First, taking a shortcut to make your life easier implies the loss of something integral to who you are, what you can be, your integrity, perhaps your honesty. Secondly, a shortcut is negative and does not help and actually hinders in the long run. Lastly, taking shortcuts by no means makes your life easier. Making your life easier, on the other hand, by taking a shortcut does not necessarily imply the loss of anything, but actually can add to knowledge, add to who you are, what you can be, is not negative, and finally does not hinder you in the long run.

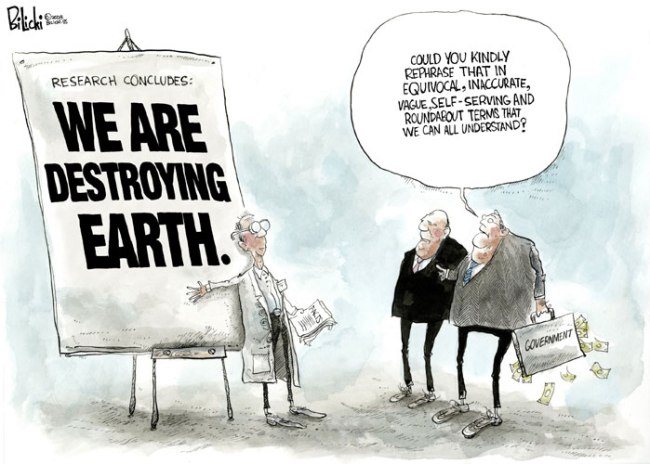

Often we take shortcuts because we think they will lead us more quickly to ease and comfort. Consider what acting on the belief that ease and comfort are innately good has gotten us today: industrial food, global economies, degrees for jobs, divorce, employment rather than careers, luxury but empty moralities, and the latest and greatest (fill in the blank). On the other hand growing your own food, buying locally, going to school to really learn something, sticking out hard times with someone you love, starting up a business based upon something you love to do, not supporting businesses that you know to be immoral, and bucking fads are all very difficult to do but they are well worth the effort; these are not shortcuts but complications. Sometimes comfort is your enemy and easy is not best; it is important to know the difference.

Shortcuts are either realizations or illusions. Taking a shortcut in order to make your life easier is creating something imaginary, something that really does not exist; making your life easier by taking a short cut is noticing reality and using it to your advantage. The first asks nothing of you and gives you nothing in return. The latter asks that you notice your surroundings and understand them. The first is motivated by ease and comfort for their own sakes, the latter is motivated by intelligence, curiosity and efficiency. The first tries to cheat reality while the latter tries to understand it.

There is an old moral adage that states that once we have knowledge of our wrong-doing then we also have the duty to change how we act. Taking a shortcut to make your life easier is somewhat different than this old adage. It, in essence, states: once we have knowledge, disregard what we know and act in any way we see fit. But I do not believe that is possible without lying to ourselves.

Unfortunately, lying to ourselves is precisely what most of us are doing as a society. We all do it and we all take shortcuts to make our lives easier. This is short-term gain at the cost of long-term happiness. I believe we know this too, and yet we continue hoping that somehow this short-cut that we have created will lead us back to the original path, the path that we ought to have never left. It will not I am afraid lead us anywhere until we being to realize that making our lives easier is really not what we want at all but rather we want to make our lives more meaningful; and there is no shortcut to that.